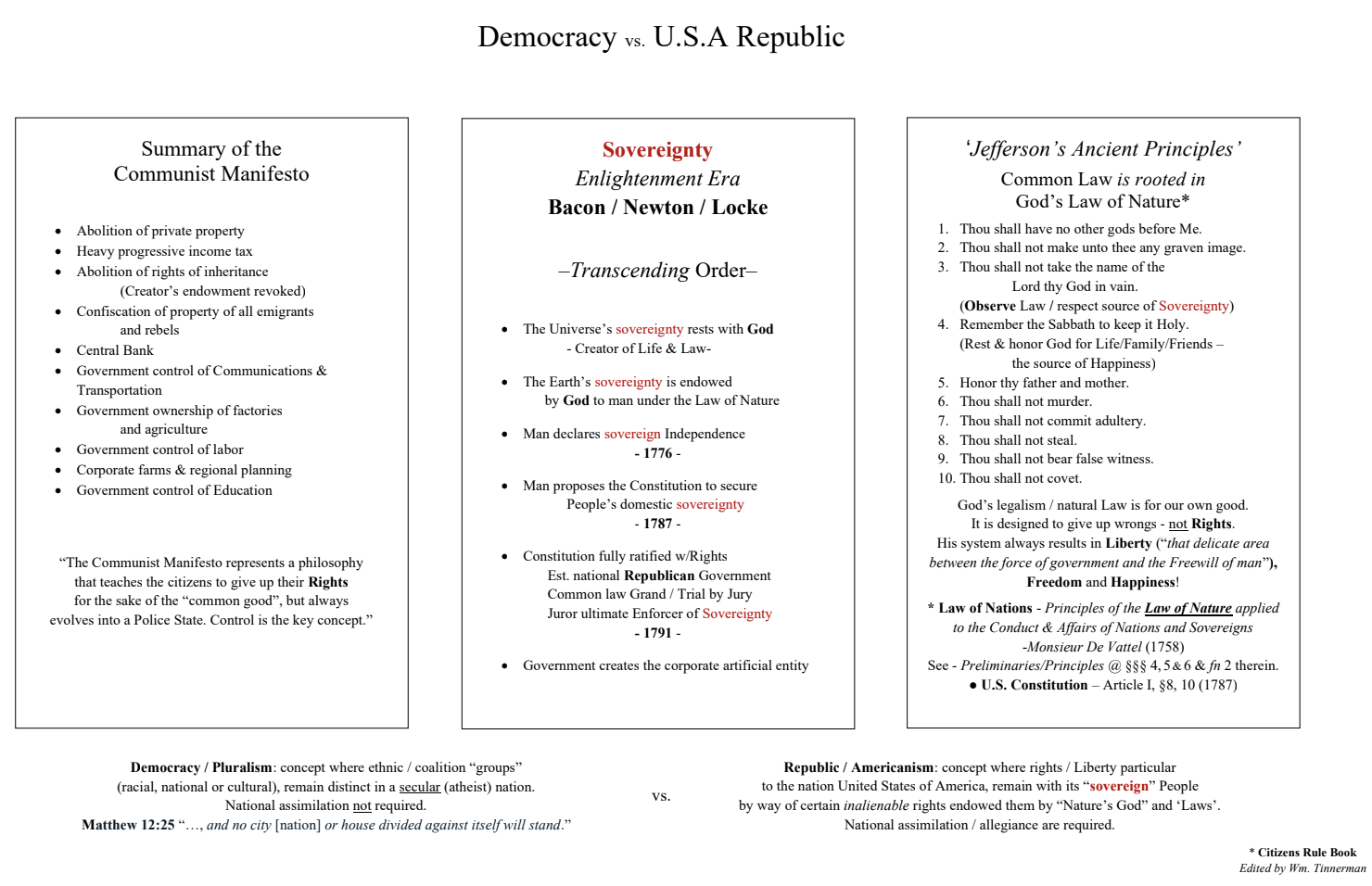

Butchers’ Union Co. v. Crescent City Co., 111 U.S. 746 , 756-757 (1884) “Inalienable Rights“

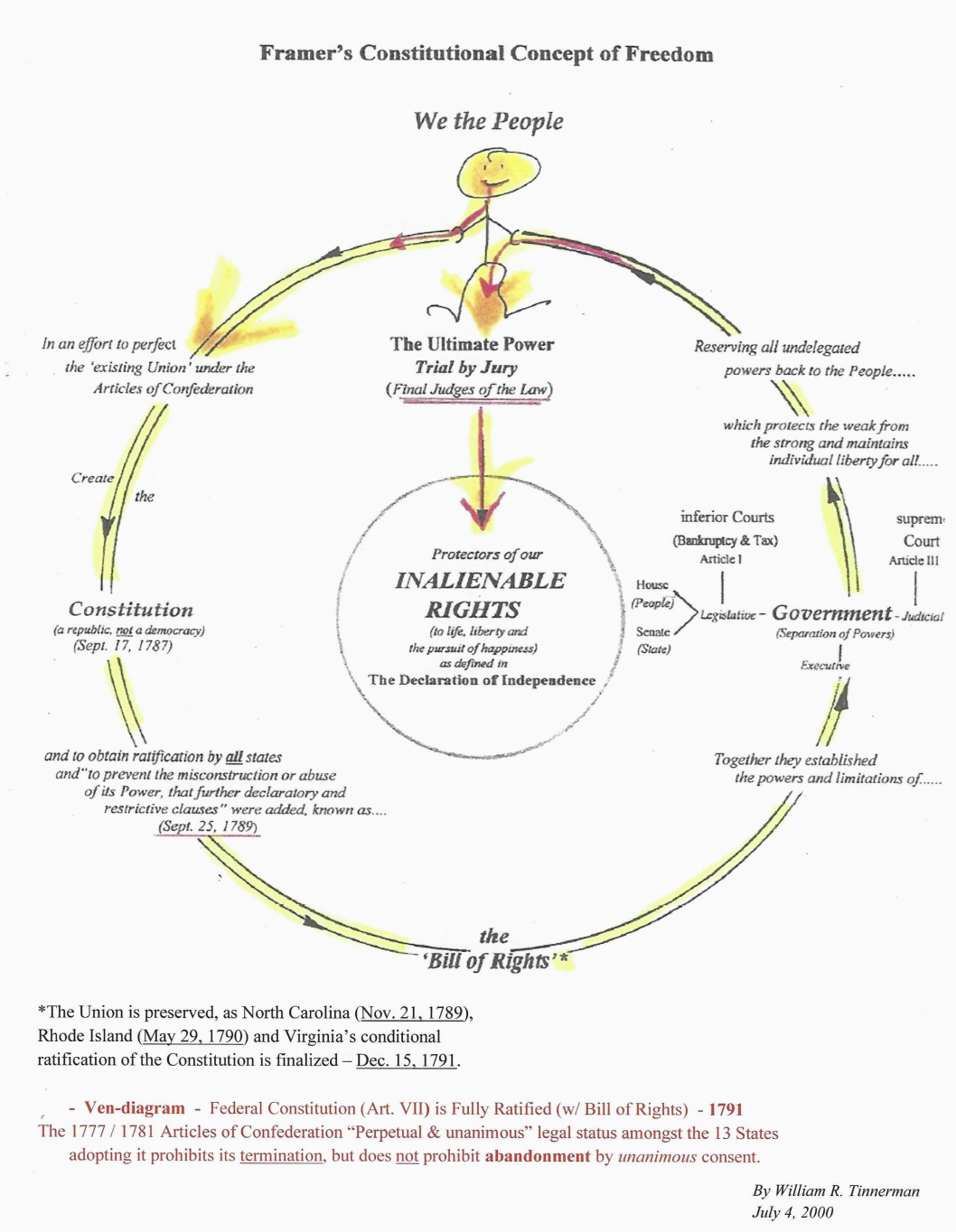

As in our intercourse with our fellow men, certain principles of morality are assumed to exist without which society would be impossible, so certain inherent rights lie at the foundation of all action and upon a recognition of them alone can free institutions be maintained. These inherent rights have never been more happily expressed than in the declaration of independence, that _new evangel of liberty to the people: “We hold these truths to be self-evident” — that is, so plain that their truth is recognized upon their mere statement — “that all men are [111 U.S. 757] endowed” — not by edicts of emperors, or decrees of Parliament, or acts of Congress, but “by their Creator with certain inalienable rights” — that is, rights which cannot be bartered away, or given away, or taken away, except in punishment of crime — “and that among these are life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness, and to secure these” — not grant them, but secure them — “governments are instituted among men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed.”

Among these inalienable rights, as proclaimed in that great document, is the right of men to pursue their happiness, by which is meant the right to pursue any lawful business or vocation, in any manner not inconsistent with the equal rights of others, which may increase their prosperity or develop their faculties, so as to give to them their highest enjoyment.

The common business and callings of life, the ordinary trades and pursuits, which are innocuous in themselves, and have been followed in all communities from time immemorial, must therefore be free in this country to all alike upon the same conditions. The right to pursue them, without let or hindrance, except that which is applied to all persons of the same age, sex, and condition, is a distinguishing privilege of citizens of the United States, and an essential element of that freedom which they claim as their birthright.

YICK WO v. HOPKINS 118 U.S. 356, 370 (1886) “Sovereignty“

“When we consider the nature and the theory of our institutions of government, the principles upon which they are sup- [118 U.S. 356,370] posed to rest, and review the history of their development, we are constrained to conclude that they do not mean to leave room for the play and action of purely personal and arbitrary power. Sovereignty itself is, of course, not subject to law, for it is the author and source of law; but in our system, while sovereign powers are delegated to the agencies of government, sovereignty itself remains with the people, by whom and for whom all government exists and acts. And the law is the definition and limitation of power. It is, indeed, quite true that there must always be lodged somewhere (the People), and in some person (the Juror) or body (the Jury), the authority of final decision; and (but) in many cases of mere administration, the responsibility is purely political, no appeal lying except to the ultimate tribunal of the public judgment, exercised either in the pressure of opinion, or by means of the suffrage. But the fundamental rights to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness, considered as individual possessions (as is sovereignty), are secured by those maxims of constitutional law (stop) which are the monuments showing the victorious progress of the race in securing to men the blessings of civilization under the reign of just and equal laws, so that, in the famous language of the Massachusetts bill of rights, the government of the commonwealth ‘may be a government of laws and not of men.’ For the very idea that one man may be compelled to hold his life, or the means of living, or any material right essential to the enjoyment of life, at the mere will of another, seems to be intolerable in any country where freedom prevails, as being the essence of slavery itself. … “

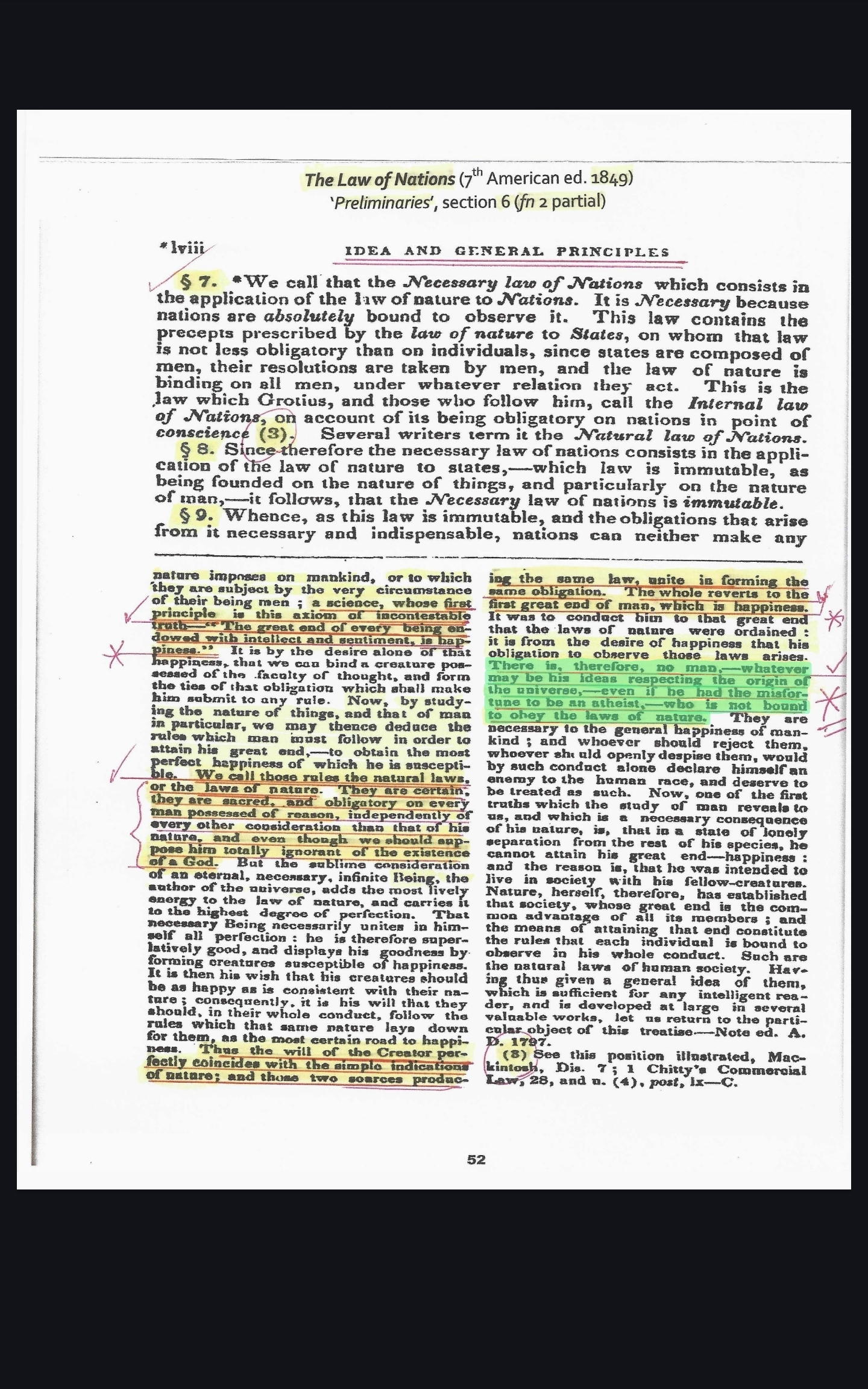

“There is, therefore, no man – whatever may be his ideas respecting the origin of the universe, – even if he had the misfortune to be an atheist, – who is not bound to obey the laws of nature.”